Map of Zimbabwe

Biologists and historians both agree that change is the only thing that lasts, and that species and cultures which seem to be ancient and eternal may vanish in the future - or may already be on their way out. The dinosaurs dominated the surface of the earth three times longer than the mammals have, while societies which endured for thousands of years, such as the Incas or the Egyptians, have either been obliterated or changed so completely that only a linguist can find any connection with what came before. During the twentieth century the pace of change has accelerated. For example, the British and the Belgians once controlled enormous parts of the earth, but now their colonies have become independent states such as Zimbabwe and Zaire, and those states seem likely to disintegrate even faster. Why is this happening, and how long will it continue? The disaster in Zimbabwe has been in the news a great deal lately, so I thought it would be interesting to look at it further.

Map of Zimbabwe

Where is Zimbabwe? The country itself is in the center of the southern cone of Africa, with high plateaus on one side and low plains on the other. Zimbabwe is completely landlocked, but it does have several large rivers and enough rainfall to support forests and savannas.

How did Zimbabwe begin? Archeologists have found stone tools in Zimbabwe which date back at least half a million years. This is older than the human species itself, so we can honestly say that people have been in Zimbabwe as long as people have existed. The oldest race we can identify, however, are the San, the Bushmen whom some readers may remember from the movie, "The Gods Must Be Crazy." The San have always been quick and light, and expert hunters. However, the San never learned to grow crops or herd animals, and the San never learned to turn metal into tools or weapons.

Unfortunately for the San, other people did. During the Fifth Century AD, at about the same time that the Roman Empire was retreating from Britain, the Bantu peoples in what we now call Congo began making iron tools and weapons. Some historians say that the critical change began when the Bantu began using iron tools for farming, growing gourds and cassava and other garden crops. This, they say, allowed the Bantu to increase their numbers and expand into new areas. Other historians say that everything changed when the Bantu learned how to make iron into swords and spears and kill rivals who only used wood and stone weapons, like the San. To my point of view the distinction does not matter, because more food and better weapons are both useful to invaders. The Bantu spread into what we now call Zimbabwe and defeated the San, so that the remaining San were only able to live in deserts so empty that the Bantu did not want them.

Ancient Tower in Zimbabwe

The Bantu then built their own civilization in the area, and the most famous of the new Bantu states are known as the Karanga. At a place called Great Zimbabwe, the Karanga state built a series of high stone towers. Many of these towers still stand, and their remains are tall and hollow but have no arches or domes on top, so that what is left of them look like giant vases. Some archeologists believe the towers were used for storing grain, and they do resemble modern grain silos at least a bit, and some archeologists believe the towers were used for defense, though they do not have windows, or bastions on the top. Whatever the towers were, they are completely different from anything in Europe and Asia, and many scholars have used them to show that Africans have been able to invent and complete their own architecture.

The Karanga were quite accomplished in other areas, and their trade routes stretched all the way to the Indian Ocean. Today the ruins of Great Zimbabwe contain many artifacts, including statues of stone hawks, and one of these statues can now be seen on the flag of Zimbabwe. The Karanga state lasted for centuries, but in the sixteenth century the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean and began monopolizing the trade, thus removing the Karanga's main source of revenue. The Karanga state fell, and the survivors regrouped into a series of confederations, such as the Rozwi empire, but they were no longer wealthy enough to build towers.

The descendants of the Karanga are the Shona, who make up about seventy percent of the nation. Next to them are the Ndebele, who make up about twenty percent of the population. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Ndebele originally lived further south in Africa, but were defeated in wars by the Zulu king, Chaka Zulu. The Ndebele then invaded what we now called Zimbabwe and conquered the Shona, forcing them to farm and keep herds for the Ndebele. (Some readers may remember similar events on other continents. For example, the XiungNu in Central Asia once defeated the Huns, and the Huns then invaded Europe and defeated the Romans.)

Central Africa traded with the Arabs on the coast of the Indian Ocean, but for thousands of years the area remained insulated from the best and the worst of European civilization. Europeans were blocked from entering the interior because the tse-tse fly killed the horses and oxen which carried their expeditions, while African armies used their superior numbers to kill European invaders in the usual way. As a result, the European empires had remained along the coast, like the Portuguese, or at the cool southern tip of Africa, like the Dutch, and no one had tried to control the interior.

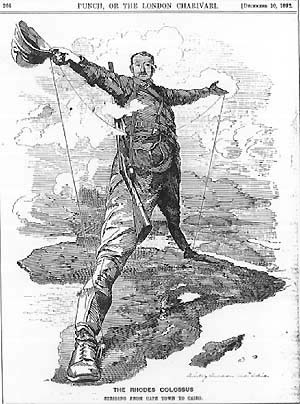

Nineteenth Century Caricature of Cecil Rhodes

Then technology advanced again, and technology changes everything. In the middle of the nineteenth century the West invented steam trains, which did not mind the tsetse fly, and the West started making repeating rifles, which made it possible for small numbers of European soldiers to defeat large numbers of Africans.

As could be expected, a handful of people saw the possibilities. Cecil Rhodes was a young British adventurer who understood what the new technologies could do, and he realized that for the first time Europeans could enter the interior of Africa they way they had entered other continents. Africa was now as vulnerable as Australia and the Americas had been for centuries.

Even in his own lifetime Rhodes was controversial. British cartoonists showed Rhodes standing on the African continent like a colossus, while he tied railroads and telegraph lines together, while on the other side of the street Marxists drew Rhodes as the quintessential capitalist bully, pounding helpless workers with an iron club. Some readers may remember that Rhodes was an obvious homosexual, but he was still well respected throughout the British business world and the British military. Some readers may remember that Rhodes was a philanthropist who created the Rhodes scholarships, which allowed students like Bill Clinton and Wesley Clark to study overseas, but Rhodes got the money for these good works by invading underdeveloped countries and extracting their natural resources.

Zimbabwe would become one of his most profitable operations. In the eighteen nineties Cecil Rhodes created a company to get gold from the territory of what we now call Zimbabwe. In the beginning, Rhodes bought mining concessions from the Shona chiefs, paying them with money, guns, or whiskey. Then Rhodes was able to bring in white settlers to help him, and within a few years he was able to rule Zimbabwe directly. Naturally the Ndebele and the Shona resisted, but Rhodes and his soldiers defeated them, and the whites created an independent state in the area, calling it Rhodesia, after Rhodes himself. The company actually ruled Zimbabwe until the nineteen twenties, when the British government finally decided to make it into a colony. Historians all agree that the Shona and Ndebele resented Rhodes and the British Empire both, and cooperated with the new regime only because the settlers had better weapons.

The fertile land of Zimbabwe became a magnet for Europeans. British farmers came in and built huge plantations to grow corn and wheat. In some places, the new farmers claimed empty land; in other places, the British soldiers actually stole the land from the Shona and Ndebele farmers and gave it to whites. Nonetheless, the new plantations prospered. The British also found coal, copper, and chrome in Rhodesia, and built mines for them as well, and they built railroads and factories and the other foundations of a modern society. As a result Rhodesia came to embody the paradox of colonialism throughout Africa; that is, the whites built things for their own benefit and managed to live like kings because of it, but their creations benefited Africans as well, and the Africans were not likely to have done it by themselves. Over the years more whites poured into Zimbabwe, until they numbered in the hundreds of thousands, while vaccines and a more reliable food supply allowed the black population to multiply as much as five or six hundred percent.

To understand the present, we must first understand the past. From the middle ages forward European society adopted a wide variety of new technologies. Gunpowder and the compass came from China, while steam engines and electricity were unique to the West, but the Europeans used them better than anyone else, while at the same time Europeans invented many forms of social organization, such stock markets and parliaments, which allowed the Europeans to coordinate their energies more effectively. And just as the Bantu used iron to dispossess the San, the Europeans used their new abilities to overcome other societies. This continued for centuries, and for centuries it become easier and easier, as the other countries simply resisted the West and tried to return to their old ways. For example, the Boxer Rebellion in China and the Great Mutiny in India were attempts to destroy new technologies, such as telegraphs and railroads, and to restore old customs, such as foot-binding and widow burning. European Empires usually defeated these without spending much in the way of money or blood.

Nonetheless, the very presence of the European empires was changing the societies that they ruled. For example, some European empires built colleges to train a governing class in the nations they conquered, and other empires simply had to train sergeants and mechanics, but in each case the conquered people were learning the new ways of doing things, and in time the other societies began to fight the West with the ideas which the West had forced on them. For example, the British tried to colonize Iraq, and they used a wide variety of weapons, including poison gas, but they could not overcome the Iraqi resistance. Instead of conceding completely, the British brought in a nobleman from Saudi Arabia and made him the new ruler, so that they were able to retain influence, but it was a far cry from direct rule. In India the situation was even more challenging, as the lawyer and seer Mohandas Gandhi studied the ideas of Thoreau and Tolstoy, and began his policy of peaceful resistance. After many years Gandhi was able to force the British to leave the subcontinent completely.

The same changes began to come to Africa. In Kenya several independence movements arose. The most formal belonged to Jomo Kenyatta, who had a British education but spent years in British prisons, while in the countryside the Mau-Mau rebels burned and terrorized British plantations. The British were able to suppress the Mau-Mau, but only by using mass torture and mass executions, and British society was no longer willing to permit this. Therefore, the British agreed to give Kenya independence by nineteen-sixty five. Rather than allow the same problem to arise throughout their other colonies, the British decided to leave Africa completely. The British proclaimed that they would leave Rhodesia at the same time, and allow the millions of black Africans to govern the country.

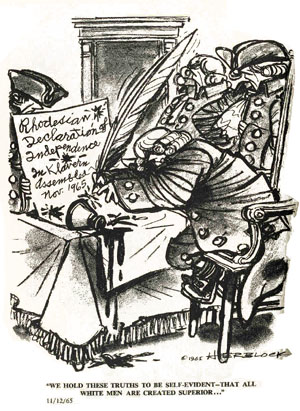

American Caricature of Ian Smith and Associates

The white Rhodesians liked the idea of independence, but they did not want to live in a country that was ruled by blacks. Therefore, the white Rhodesians went into rebellion against the British empire and declared that they were now an independent state, dedicated to white supremacy. After all, the white settlers had controlled Rhodesia before, and they believed that they could do it again. Nonetheless, no nation in the world supported them. The British put sanctions on the new Rhodesia, and over the years more nations would join the sanctions until most of the world refused to trade with the new republic.

As could be expected, the blacks in Rhodesia did not like white rule. The Ndebele formed their own army of resistance, calling it the Zimbabwe African People's Union, or ZAPU; and the Shona formed a different army, which they called the Zimbabwe African National Union, or ZANU. The whites and the blacks fought for more than ten years, and thousands of people were killed, often in horrible circumstances. For a while the war and the sanctions actually encouraged the economy, because the whites built factories to make the products that they could not buy overseas, but in the long term the whites grew discouraged at the constant violence, and greater numbers began to move to other countries. At the same time the Soviets sent weapons to help the black armies.

By the end of the seventies the whites were defeated. In nineteen-eighty the whites signed a treaty with the blacks. For about six weeks Rhodesia became part of the British empire again, and the British held new elections. Rhodesia then became independent for a second time, and adopted its current name, Zimbabwe. The leader of the Shona army, Robert Mugabe, became the new president.

For a brief moment everything looked good. In nineteen eighty the African continent had fifty independent states, but fewer than five were self-sufficient in grain, while Zimbabwe grew so much food that the nation was able to export it. At the same time few African states had any industry, and most ran up large foreign debts importing manufactured goods. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, had a wide variety of factories. Many African states were so chaotic that foreign corporations avoided them, but Zimbabwe had a clean and modern infrastructure. During the independence ceremonies the president of Tanzania told the president of Zimbabwe "You have the pearl of Africa in your hand. Don't break it!" A wide range of experts thought that Zimbabwe was ideally situated to do for Africa what Hong Kong would do for China, and become a funnel to allow First-World money and technology to enter the continent.

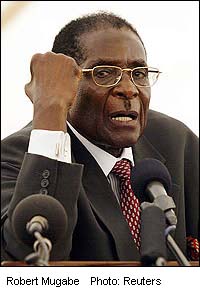

Dictator Robert Mugabe

As we have already mentioned, things did not work that way. The situation started to go downhill almost immediately. Mugabe wanted to take away the white farms and businesses, but the treaty said he could not. Instead, the British government suggested that Mugabe should buy the farms, and every year the British gave Mugabe millions of dollars to buy the buy the land and distribute it to blacks. Unfortunately, Mugabe did not buy any farms; instead, most of the money went directly to his own supporters. In a few years Mugabe began to quarrel with the Ndebele. Fighting between the two tribes last for three years, but even when it was over bad feeling remained. At the same time the new officials began to seek their own interests in bolder and more open ways. Zimbabwe became more corrupt, and crime escalated. Tens of thousands of whites left Zimbabwe and went back to England, or to South Africa. Many blacks were glad to see them go, but the blacks did not know how to operate the mines and businesses themselves, and the economy began to collapse.

Three years ago things came to a head. The Ndebele began to rebel against Mugabe, again, and then Shona labor unions started holding strikes. Mugabe realized that he might lose power, so he responded by killing large numbers of blacks, and then by trying to buy the others off. And then Mugabe said that he wanted to go ahead with land reform, taking land from the rich and giving it to the poor.

Land reform was one of the great goals of the twentieth century throughout the world. For example, in countries like Japan and Taiwan hundreds of thousands of farmers had grown their own crops with their own hands, and then paid rent to landlords who lived far away and never even saw the land, let alone worked on it. In countries like Japan and Taiwan, land reformers simply transferred the deeds for the land from the absentee landlords to the farmers, so that the farmers could go on planting their fields without having to pay rent on them. As a result, the actual farmers continued to grow crops on the same land using the techniques which had already been proven to work, and neither the farmers nor food production suffered.

Mugabe's concept of land reform was very different. In Zimbabwe, the white farmers owned immense plantations, but they lived on them and worked on them every day, guiding the machinery and supervising the business. At the same time, thousands of black Zimbabweans worked for the whites, putting in generations of sweat and learning how to operate the machinery and techniques which allowed the farms to grow so much food. Mugabe drove off the white farmers, but he did not give the land to their black workers; instead, he drove the black workers off too, often with worse violence than he used on the whites. Mugabe then began giving farms to his own friends, and to his supporters; and when they had enough he started giving farms to young men from the cities, many of whom had never even seen a plow, let alone run a farm. The crops all died, and the fields went to waste.

Today the newspapers are filled with disaster stories from Zimbabwe. Recently one part of the country flooded, and a woman was televised giving birth in a tree, while Mugabe flew his personal helicopter to a market and bought watermelons for himself. The lights are out and people fight for gasoline, while the currency has become so weak that people actually have to carry money in baskets to buy bread. HIV is rampant, as it is in many other African countries, while even the dead are not safe, because criminals are now earning money by digging up graves and selling the coffins to new users. Most mines and factories have stopped operating. Poachers now hunt impalas and other wild animals in what used to be private game parks. The international community has been sending grain to feed the hungry, but many people complain that Mugabe is only allowing the Shona to get it, while trying to starve the Ndebele and anyone who does not support him.

The war for Rhodesia was a brutal war. The whites rode on horses and chopped people up with swords, and they made all of the Western nations ashamed. I was glad when the war ended, and I believed that a new country could be built where whites and blacks could work together and everybody would have a fair chance. Clearly, this did not happen. Instead, Zimbabwe is following the same path as other African republics, such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, which have declined steadily ever since they went to majority rule.

Why? On the left, some people blame what they call 'the shackle wounds of slavery.' These people say that white rule damaged African culture and society so badly that the Africans have become unable to work together. On the right, many people say that the Europeans brought new technologies and institutions to Africa without giving the Africans time to understand them, rather like the Romans did to the British, when they invaded Britain thousands of years ago. Which is correct -- both, or some third answer? I am always open to new points of view.

Copyright 2003 Dan Willmore